In Peter Pan, Wendy and Peter navigate to Neverland by following the “second star to the right and straight on till morning.” If all problems of navigation were so simple! Down through history sailors and explorers on land have sought functional ways to 1) know where they are at present and 2) to steer a course to a destination. In the earliest of times sailors followed the coast to get from place to place and used the sun as a basic guide. The discovery of the compass allowed sailors to cross oceans and scouts to navigate the woods. I want to briefly discuss two points in the history of navigation: Today (2021) and two hundred years ago (1821).

In 1821, science and engineering had provided tools for navigation that were practical, allowed for fairly accurate navigation and that are still in use today, albeit only as a back-up when the battery in one’s iPhone needs charging and no electricity is available. I’m going to go into the 1821 tools second.

First, today’s marvel is that aforementioned iPhone (or other current phone). On the left is a photo of the screen of my iPhone. It shows my RL house. The blue dot at the top locates me (or more accurately my phone) within a few feet of where I actually am. The other dot shows my car parked in the garage. My phone noted the car’s position when I parked. This functionality works automatically. All I do is launch the Maps app and my phone shows me where I am and will guide me to wherever I want to go.

It was more complicated in 1821. Below are the tools one would take on a voyage by sailing ship in the early 19th century

Compass – Points to the magnetic North and provides guidance in setting one’s direction.

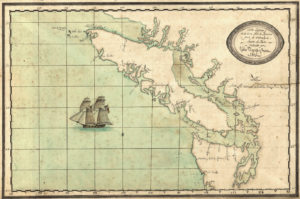

Charts – Used in conjunction with the compass as an aid in choosing the direction to go. Chart from the early 19th century below. This chart lacks the detail found on modern charts but at one time it was all that was available.

Chip Log – Used to estimate speed through the water. Speed estimates let one record progress on the chart. The triangular piece of wood was tossed overboard and as the ship pulled away from it, the string was unwound. A small sand glass was used to time the test and the length of string pulled out was determined by counting knots tied along the string. The nautical term, knot, as a measure of speed (nautical-miles-per-hour), may have been derived from the knots in the string.

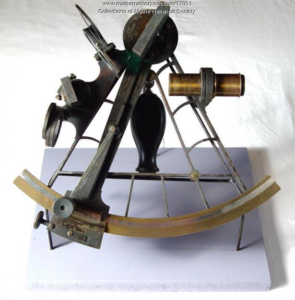

Sextant – Used in 1821 to determine the latitude by measuring the angle between the sun at noon and the horizon. The sighting is converted to a line of position, that can be plotted on a chart, using a series of equations and tables. The ship is somewhere on that latitude line. In more recent times, the sextant can also be used for an estimate of position by making multiple observations of the sun and moon or particular stars. This method creates several lines of position and where the lines cross is one’s location. This method identifies both latitude and longitude simultaneously.

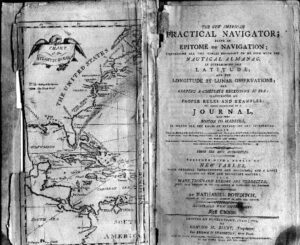

Bowditch’s New American Practical Navigator – A guide to celestial navigation and tables for calculating one’s latitude from a sextant’s observation. It also explained how to estimate latitude from observing the moon. It was the best resource in 1821 and, much revised, is still published today.

Bowditch’s New American Practical Navigator – A guide to celestial navigation and tables for calculating one’s latitude from a sextant’s observation. It also explained how to estimate latitude from observing the moon. It was the best resource in 1821 and, much revised, is still published today.

Chronometer – An accurate clock, set to Greenwich Mean Time. Greenwich is the 0 longitude and if one knows the time in Greenwich and the local time, it is easy to determine one’s longitude. For example: Noon in Texas is 6pm in Greenwich. Every hour West of Greenwich is 15 degrees longitude, so Texas is 90 degrees West of Greenwich.

Using all of these tools correctly and carefully can result in a calculated position accurate to about two tenths of a nautical mile or about 400 yards. Not as good as my phone but good enough to navigate the world.

References

- Peter Pan, or The Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up, J. M. Barrie, 1904 (play), 1911 (novel), Hodder & Stoughton.

- Celestial Navigation, Wikipedia.

- History of the Compass, Wikipedia.

- Chip Log, Wikipedia.

- Nautical Chart, Wikipedia.

- Bowditch’s American Practical Navigator. Free copy of the 2017 edition is available from the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency. (Also available are free digital nautical charts).

- Navigation by Sextant, NOVA Online. If you visit this page, back up to the section on Shackleton’s voyage. It is a classic tale of navigation across icy seas in a desperate, but successful, quest to save the lives of a ship’s crew.

- Sight Reduction, Wikipedia. Sight reduction is the mathematical process of deriving from a sight (say of the sun) the information needed for establishing a line of position.

- Obsessed With Time, Hypothesis!, Science Circle, January 2020.

- Solving the Problem of Longitude, Burkholder, R., Captain Cook Society.

Image Credits

- Chip Log, Photo by Rémi Kaupp, CC-BY-SA, Wikimedia Commons.

- Nautical Chart from 1808, University of Washington Libraries.

- Bowditch 1802 edition cover page. See page for author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

- Spencer, Browning and Rust of London, England, “1830’s sextant,” HST 325 – U.S. Foreign Relations to 1914 (MSU), accessed December 29, 2020.

- Compass and Chronometer photos by author.

|

| Visits: 37 |

It is fascinating the tools necessary for navigation before the GPS. The skills required for using those tools should never be lost, given that GPS may not last forever, or you may at times find yourself bereft of a GPS receiver. Interestingly, Polynesian sailors could navigate the entire Pacific Ocean without such tools.

One correction: knot = nautical mile per hour. You wouldn’t say “knots per hour.”

Thank you for your correction. I’d not noticed that redundancy.