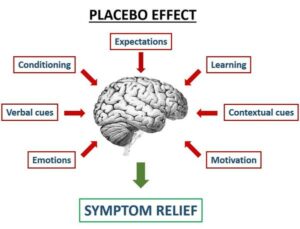

Early clinical research was simply trying a new cure and seeing if patients got better. This method was very limited because people tend to heal over time regardless of interventions. The fact that humans are living organisms with strong powers of self-healing complicates the process of testing methods to improve healing. Over time researchers developed control groups. This allowed subjects taking the treatment to be compared with subjects who did nothing in particular but would show any improvement due to nature and the passage of time. Eventually, researchers figured out that just being in a study, this being a change in behavior, often made people get better. Finally, research designs were created that attempted to match the experience of the control group with the treatment group. People in the control group had exactly the same experience as the treatment group, except the medicine was something totally neutral and harmless. Thus, if the treatment group was different from the controls, then the effect was due to the medicine and not extraneous variables like expecting change, natural healing, being in a study or taking something. This neutral and harmless treatment is a placebo.

Simple example. Humans are complicated organisms and any single condition is the product of a multitude of variables. Take the question of does aspirin cure a headache? We all get headaches at times and they appear to be caused by many sources, a cold, stress, being tired, etc. Often if we just relax for awhile the headache goes away. Sometimes a glass of water. Taking a walk. A nap? Many things seem to help but what about taking two aspirin tablets? What if we think we took an aspirin tablet? Turns out that thinking one has taken something to cure a headache can affect the headache. That’s a placebo effect. In order to see of aspirin really helps we need to compare groups of people, one which takes aspirin for a headache and another that takes a tablet that contains nothing beneficial but harmless and involves the same behaviors and expectations as taking an aspirin. This allows us to see the effect of expectations without an active treatment compared with the actual treatment and to more accurately assess the utility of the treatment.

Just comparing an active treatment and a placebo treatment is not quite enough to fully test the case. There is a difference between no-treatment control groups and placebo treatment groups. Good clinical research studies need to have both no-treatment and placebo groups.

Just comparing an active treatment and a placebo treatment is not quite enough to fully test the case. There is a difference between no-treatment control groups and placebo treatment groups. Good clinical research studies need to have both no-treatment and placebo groups.

Some articles on placebos look at the placebo as a treatment rather than placebo as control. For example, two studies, Valerie Yeung et al (2018) and Raveendhara R. Bannuru et al (2015), look at the effects of various placebos compared to no-treatment groups. The article from Like Iron (2018) cites several studies looking at the effect of a placebo on strength training.

How large can the placebo effect be? This is a difficult question and the paragraph below from Linde, Fässler & Meissner (2011) provides insight into this issue.

“An analysis of the proportion of patients reporting satisfactory relief after receiving placebo in 15 controlled trials published by Beecher in 1955 in JAMA (The Journal of the American Medical Association) is probably the most cited article in the field of placebo research. This article is the basis of a widely quoted myth that the average size of placebo effects is about 35 per cent. … In 1994, a major review published in JAMA claimed even larger placebo effects based on the improvement in placebo groups. A careful re-analysis of the original studies included in Beecher’s review concluded that spontaneous improvement, fluctuation of symptoms, regression to the mean, additional treatment, response biases and misquotation were plausible alternative explanations for the presumed placebo effects. These reasons also explain why it is almost impossible to reliably judge in routine clinical practice whether a placebo effect has occurred. A recent analysis of trials including both a placebo and no-treatment control group also found relevant improvement in many no-treatment groups. In conclusion, changes observed in patients receiving placebo over time are not a reliable way to estimate the size of placebo effects.”

- Placebo effect studies are susceptible to response bias and to other types of biases, Asbjørn Hróbjartsson, Ted J Kaptchuk and Franklin G Miller, J Clin Epidemiol, Nov 2011, 64(11), 1223–1229.

- A systematic review and meta-analysis of placebo versus no treatment for insomnia symptoms, Valerie Yeung et al, Sleep Medicine Reviews, April 2018, 38, 17-27.

- Effectiveness and Implications of Alternative Placebo Treatments: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis of Osteoarthritis Trials, Raveendhara R. Bannuru et al, Annals of Internal medicine, September 1, 2015, 163, 5, 365-372.

- Placebo interventions, placebo effects and clinical practice, Klaus Linde, Margrit Fässler, and Karin Meissner, Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci., June 27 2011, 366(1572), 1905–1912.

- The power of the placebo effect, Harvard Men’s Health Watch, Harvard Medical School, Updated: August 9, 2019Published: May, 2017. Lay article discussing the placebo effect.

Image Sources

- The Placebo Effect and Strength Training, Like Iron, July 17, 2018. This article and graphic was located for me by Caasi Malachite. She was my Editorial Assistant at MANIERA Magazine.

- Deepy is considering some pills… treatment or placebo? She is wearing the Fearless outfit from LUXE Paris Fashion House. The pill bottle pose is from Reve Obscura.

|

| Visits: 19 |