When I was in high school I discovered a musical piece named The Planets. It “is a seven-movement orchestral suite by the English composer Gustav Holst, written between 1914 and 1917. In the last movement the orchestra is joined by a wordless female chorus. Each movement of the suite is named after a planet of the Solar System and its supposed astrological character” (Wikipedia).

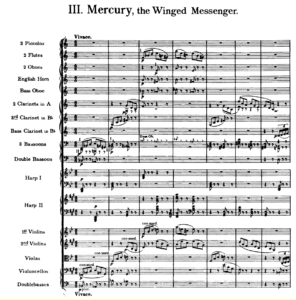

My teen-age self was familiar with each of the then nine planets from my father’s astronomy buddies and had seen most of them through various telescopes, especially the 20-inch refractor at Chabot Observatory. They were just points of light that may or may not look like a sphere. It was the music that created the magic in my mind. There is a separate movement for each planet however only seven of them as Holst wrote the piece before Pluto was discovered, and then subsequently kicked out of the Planet Club, and he left out Earth. One page of the original composition is on the right.

My teen-age self was familiar with each of the then nine planets from my father’s astronomy buddies and had seen most of them through various telescopes, especially the 20-inch refractor at Chabot Observatory. They were just points of light that may or may not look like a sphere. It was the music that created the magic in my mind. There is a separate movement for each planet however only seven of them as Holst wrote the piece before Pluto was discovered, and then subsequently kicked out of the Planet Club, and he left out Earth. One page of the original composition is on the right.

“The musica universalis (literally universal music), also called music of the spheres or harmony of the spheres, is a philosophical concept that regards proportions in the movements of celestial bodies – the Sun, Moon, and planets – as a form of music. The theory, originating in ancient Greece, was a tenet of Pythagoreanism, and was later developed by 16th-century astronomer Johannes Kepler. Kepler did not believe this “music” to be audible, but felt that it could nevertheless be heard by the soul” (Wikipedia).

Recent celestial discoveries have supported the idea of musica universalis with what is known as orbital resonance. These are orbits of planets and moons that are integer ratios. Thus, Pluto completes two orbits in the time it takes Neptune to complete three, thus a 2:3 ratio (Wikipedia). These orbits that move in harmony can be said to be the music of the spheres. An example, using Jupiter’s moons, is shown in the diagram on the right.

Recent celestial discoveries have supported the idea of musica universalis with what is known as orbital resonance. These are orbits of planets and moons that are integer ratios. Thus, Pluto completes two orbits in the time it takes Neptune to complete three, thus a 2:3 ratio (Wikipedia). These orbits that move in harmony can be said to be the music of the spheres. An example, using Jupiter’s moons, is shown in the diagram on the right.

Recently planets circling distant stars have been identified and some of these planets exhibit orbital resonance. One of these systems, TOI-178, shows six planets moving in near integer resonances. They are not exact integers and because of that the patterns may not be stable and the relationships may drift over thousands of years. Regardless, there is an animation of the planets that adds musical notes when the planets come together (conjunctions) and the result is quite musical. This brings us around from physics to art.

Holst’s music has been recorded by hundreds of orchestras since 1918 and many versions are available on the Internet. One good rendition is listed below on YouTube.

If you desire to observe the planets and outside viewing conditions are not optimal there is a nice planetarium on the Science Circle island in Second Life.

I leave you with a final thought – Never underestimate the influence of art on science.

References

- The Planets, Wikipedia.

- Gustav Holst – The Planets, Op. 32, Filharmonia Narodowa, YouTube.

- Chabot Observatory and the Eastbay Astronomical Society, Oakland, California.

- Musica Universalis (Music of the Spheres), Wikipedia.

- Orbital Resonance, Wikipedia.

- Hear the strange music of distant planetary system TOI-178, EarthSky,

January 25, 2021. - Artist’s animation of the TOI-178 orbits and resonances, European Southern Observatory (ESO), YouTube.

- TOI-178 and Laplace Resonances, Wikipedia.

Image – “The three-body Laplace resonance exhibited by three of Jupiter’s Galilean moons. Conjunctions are highlighted by brief color changes. There are two Io-Europa conjunctions (green) and three Io-Ganymede conjunctions (grey) for each Europa-Ganymede conjunction (magenta). This diagram is not to scale” (Wikipedia).

|

| Visits: 66 |